“We are the first group worldwide to have developed stem cell gene therapy for this type of SCID, RAG1-SCID to be precise. It is also the first stem cell gene therapy initiated by the Netherlands that will actually be used in patients," says Professor of Stem Cell Biology Frank Staal. The researchers have spent a total of 15 years developing the therapy and consider the opening of the study a milestone. "We can finally start and treat our first patients. Because it is a very rare disorder in new-borns, the first patient should probably still be born," says Staal.

The right donor

Severe Combined Immunodeficiency (SCID) is a rare congenital immune disorder. Children with SCID are born without essential immune cells so even a harmless common cold virus can be fatal. Without a stem cell transplant, patients die before the age of one. "When the tissue type (HLA) of the stem cell donor matches that of the patient, the success rate is very high, reaching 80 to 90%," explains Arjan Lankester, Professor of Paediatrics and Stem Cell Transplantation at the Willem-Alexander Children's Hospital.

Unfortunately, no suitable donor is available for half of the patients. "Since stem cell transplantation is the only chance of survival, we regularly have to use a donor whose HLA type only partly matches that of the patient. In this case, the survival rate is about 20% lower and the quality of life after transplantation is also reduced," Lankester continues. In addition, every stem cell transplant comes with a risk of an unwanted reaction of the donor cells against the patient's body, so-called graft-versus-host disease.

Your own donor

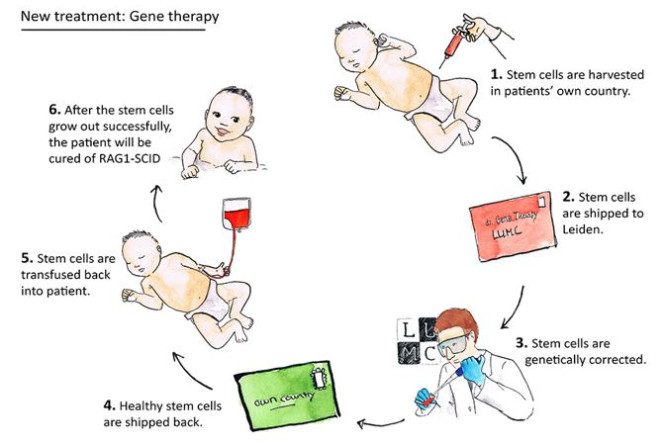

"Stem cell gene therapy can solve these problems. The patients are their own donors in this therapy," Staal explains. "The gene error that is present in the patient's stem cells is corrected in our laboratory. We do this with a crippled virus that builds a good version of the gene into the DNA of the stem cells. We then give the corrected stem cells back to the patient. A properly functioning immune system will be able to grow from these cells. We really tackle the problem at the source," says Staal.

As easy as it may sound, the reality proved to be quite difficult. Staal: "It took us almost 15 years to do this, and for good reason. The type of SCID that we focus on is caused by mutations in a very tricky gene, RAG1. We had to pull out all sorts of tricks to make it work. The more we are pleased now that we have succeeded." With this Leiden breakthrough, stem cell gene therapy is now available for the third genetic form of SCID. As a result, this therapy could eventually provide a solution for the majority of all future SCID patients.

Cells travel, not patients

During the development of this new therapy, Staal and Lankester partnered with top institutions from other European countries. "This allowed us not only to share our experiences, but also to create a unique structure that benefits patients with this rare disease," says Lankester. Whereas SCID patients and their parents have to spend several months in Milan, London or Paris for the two existing stem cell gene therapies, the gene therapy for RAG1-SCID can be made available in several European countries via the LUMC.

Unique setting

According to Staal and Lankester, the fact that the LUMC is the first academic institution in the Netherlands to develop stem cell gene therapy into a clinical application is due to the good cooperation between departments. "LUMC offers a fantastic setting where all fields of expertise, from researchers to doctors and pharmacologists, come together. That is one of the main reasons why we succeeded in developing this therapy," says Lankester. "This new therapy builds on the long history of the LUMC treating patients with congenital immune disorders. More than 50 years ago, the first successful European stem cell transplant in a patient with SCID was performed at the LUMC."

Wider application

The researchers are convinced that this technology can also be used for other rare diseases. "Of course, every gene is different," says Staal. "We are now investigating another SCID gene, RAG2, which appears to require a different approach. But I am confident that we can develop this further into a versatile therapy for a wide range of conditions, including other immune and metabolic diseases for which no optimal treatment options are yet available."

Click here to listen to the radio broadcast.